Chinese Heritage Stories

These brief vignettes are but a few of the stories that shed light on Chinese life, culture and contributions in the Lower Columbia River Basin.

Tongs | See the video

Tongs | See the video

Tongs were a social organization that also served to provide order for the Chinese community. Tongs did not exist in China and were unique to the Chinese immigrant society. They have had both positive and negative connotations — either as a protective social organization that looked after and protected the Chinese immigrants, or as a center for organized crime whose income was made largely from the “vice” industry.

Tongs in Astoria formed as early as the 1870s, and there grew to be as many as eight or nine. Large amounts of money were made by some of the Tongs, and around the turn of the century violence was often the result of struggle for control over gambling, drugs and prosititution. By the 1930s, as the Chinese population declined in number, the Astoria tongs began to disappear. The remaining Tongs became known more for their benevolence than violence.

The Barber Lady | See the video

The Barber Lady | See the video

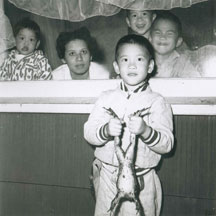

Born in 1902, Sing Hee Leong emigrated from China to Seattle, eventually making her way to Astoria in the 1920s. In interviews with Chinese elders, it was discovered that some did not even know or remember her given name. She is affectionately remembered as “Jin Mo Sum” (The Barber Lady) because she was most noted for her role in the community as the woman who gave haircuts to the Chinese immigrants.

Many admire her for her ability to raise her son under difficult conditions, as a single mother in a male dominated society and during a time when being of Asian descent was a significant social obstacle. She was able to accomplish this through hard work, determination, and perseverence.

Not only was she a barber, she was known throughout the community for her laundry and cooking skills. In later years, after the barber shop was closed, she became known for her almond cookies and would bake them by the box load for family and friends.

Sing Hee Leong is surived by her son Victor Kee and her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Victor Kee, his son Robert Kee and their families still reside in Astoria.

Lum Quing Grocery | See the video

Lum Quing Grocery | See the video

Lum Quing emigrated from a village south of Canton, China during the 1890s. He started out as a gardener but longed to have his own store. His brother, Lum Sue from California, joined Quing in Astoria to open the business.

The original store was built in 1908 and was located around 9th and Bond. It was destroyed by the fire of 1921 and was rebuilt in 1922 at a new location on 6th and Bond. During this time, the store was owned and operated by Lum Sue and it served the community well. In the mid-1930s Mr. Lum suffered a stroke and the store was run by his son Johnny and wife Clara, with help from a relative named Peter. The store continued to operate even after the Chinese population dwindled and larger stores moved into town. Lum Quing grocery finally closed in 1964 after 42 years in operation. This store's final location eventually became the home for Toyota of Astoria with David Lum a founding partner.

Astoria Chinese School | See the video

Astoria Chinese School | See the video

Education was very important to the Chinese immigrants, and while they believed strongly in assimulating to the American education system, they also believed in the preservation of their own culture.

The Astoria Chinese School was established and located at 6th and Bond across from the Bing Kung-Bo Leong Tong. Astoria'a public schools served as the primary means of education, while the Astoria Chinese School was open to students in the evenings and on Saturdays. The school's first and only teacher was Mrs. Jeanette Lee. She was the sister-in-law to Wong Lam, one of Astoria's Chinese labor contractors. She is remembered as a very good but strict teacher The school operated continuously from 1913-1923.

Lee Sing | See the video

Lee Sing | See the video

This is a story of a Chinese immigrant who, like many other immigrants of this time period, came to America hoping to make his fortune and return to his wife and family in China. Unfortunately, this never happened.

For years the local Chinese supplied the community with produce. Lee Sing was noted for his gardening skills and is known locally as the last “Chinese Gardener.” He had a small store where he also lived with his pets and raised his chickens. He often had to clear his counter of the fowl to serve his customers.

Lee Sing was a very talented man, and was probably most noted for his craftmanship, hand carvings, and ability with clocks. He repaired clocks with great skill and often built coo-coo clocks using everyday materials for the frame and paper for the bellows. Harry and Margaret Miller knew Sing well, and to this day have an operating clock that he fixed for Margaret's family in the 1920s. The repair features a wooden dowel hand-carved to replace the original part that was missing or broken.

Lee Sing was equally popular with all the locals. Although he lived a simple life, he was very generous, good natured and enjoyed many friends. He was featured in a story, published in the Summer of 2009 Cumtux magazine, inspired by many past neighbors and friends. He passed away in 1972 but is still well remembered today.

Canneries | See the video

Canneries | See the video

Working in the salmon canneries was one of the best-known activities of the Chinese in Astoria. Their ability to handle butcher knives and work long hours were quickly recognized by the salmon packers, who in turn hired Chinese contractors to put together Chinese crews for the jobs. When the fish came in, these crews worked rapidily and efficiently to butcher and clean the salmon for canning. When the Salmon runs were at their peak in the early 1900s, the population of Chinese workers could swell to 3000.

The use of Chinese labor in canneries dwindled for several reasons. First, it mirrored the decline in the salmon runs through the early 20th century. Second, the constant desire to economize production brought the advent of automated packing equipment, often referred to as the “iron chink.” The machine was invented in the early 1900s, and earned its derogatory name for the workers it would displace.

The declining labor pool was also the result of federal legislation. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made Chinese immigration difficult, so by the early 1900s the pool of first generation immigrants was aging while the second generation was beginning to find jobs in professional fields. By World War II, Chinese contract labor was nearly non-existent.

Bull Frogs | See the video

Bull Frogs | See the video

Few people have heard the story of how the Lousianna Bull Frog was introduced to Clatsop County.

The story that has been passed down takes place in the mid-1930s, when Edward Yim Lee hoped to make his fortune trying to raise and sell this delicacy to restaurants and fine food stores. Afterall, the legs of this amphibian taste like chicken and had a lot less bone.

He imported six pairs of frogs from Louisiana, and set out to build his frog farm along the shores of the Knowland Slough where it crosses Youngs River Road (approximately 1/8 mile east of Miles Crossing). He attempted to keep his pen secure, but within two years his stock of frogs dwindled and all the tadpoles had escaped. Shortly after, his plan of raising frogs was abandoned. Years later it became natural to hear the familiar sound of these honking frogs, from dusk to dawn, near every local lake and slough in Clatsop County.